The Conan and Robert E. Howard Website |

||||

| |

The Conan and Robert E. Howard Website |

||||

| |

by Edward Waterman (Copyright © 1999 Edward Waterman - All rights reserved)  Behold, Myth Maker! The first offering from Cross Plains Comics. This upstart is a brand new comic book company created to adapt the prose and poetry of legendary fantasy, horror, and adventure author, Robert E. Howard, into the sequential comic art form. Myth Maker is a wonderfully designed and crafted comic book. The text used for the stories is taken directly out of the original texts by Robert E. Howard, with only very few exceptions. However, this is not to say that the complete text from Howard's stories appeared in Myth Maker. Due to the limitations of space and the nature of the visual medium, the amount of text in a comic book adaptation will usually be far less than found in the original short story or novel. So, the text we see in Myth Maker is a cut down version of the stories where only the most important elements of Howard's storytelling were retained. Since one would be hard pressed to even find a Robert E. Howard tale that contained text that is inessential or unrelated to the drama of the story, the goal for the comic book creators is not to get rid of extraneous text. You won't find any. Instead the goal is to form an outline of the story in a way that will convey the meaning and emotional impact of the original tale, preferably in the author's own voice. Balancing the limited amount of available space, the need to capture the essence of the story, and the demand to provide an exciting and dramatic re-telling is the Damocles Sword of comic book adaptations. Not only does the comic book writer need to have an intimate and in depth understanding of the original tale, but the writer ought to have an unerring sense of drama. Perhaps above all, the writer must appreciate how the original author attempted to accomplish the same dramatic goals in his medium, with a keen eye on word choice. The omission or addition of even one word could mean all the difference between a story which is interesting and exiting, and a story which is confusing and dull. Of particular importance are adjectives and other key words which help identify characters, establish settings and moods, and retain the continuity of events in a story. If a comic book writer falls short of conveying the drama of the original story, the likelihood is that the short-fall will be found in one of the areas just discussed. Given the delicacy and difficulty of condensing and adapting a story successfully, one might be persuaded to generalize that all comic book adaptations will pale in comparison to the original story. It's not that bad, however. The visual imagery of the comic book medium can help tell and even enhance a story. An ancient Chinese proverb says that one picture is worth more than a thousand words, and I never argue with the ancients! Aside from a little bad of humor, the point here is that it is possible for comic art and imagery to fill in any holes created from the compression of the original story. In fact, images can often be used to replace text, especially descriptive text, without any lessening of dramatic effect. All this speaks directly to the idea of the artist as storyteller. In some cases, the artist may even be the primary story-teller and the text may simply be used to support the images. This illustrates the fact that the creation of a comic book story is a collaborative process where both the writer and the artist share the responsibility of telling the tale. Even so, we can not excuse the editor from this process. The editor is the overseer and the coordinator. He is the person who judges, evaluates, and approves the final draft of the comic book story. He may be the only person who has seen the art combined with the story text, and as such has an awesome responsibility to make sure that all of the pieces of the story fit together to tell the best story possible. The editor also needs an unerring sense of drama, a superb sense of visual excitement, and a tremendous knowledge of story-telling himself so that he can determine when a comic book story needs more work and when it doesn't. If a mistake in a story is made by an artist or writer but is never-the-less approved by the editor, then the editor dropped the ball. He didn't properly exercise his role as master story-teller. The critique below addresses each section of the comic book by story, poem, article, etc. This review will focus primarily on the ability of the adaptation to convey the essence of the original story and to provide an exciting and dramatic re-telling... with room for other comments as well. Stories: The three stories which were adapted, "Spear and Fang," "Dream Snake," and "Dermod's Bane," are some of Robert E. Howard's shorter stories, consisting of only eight pages each. As a group, these stories represent some of Howard's lesser work, but they were never-the-less well-crafted dramatic tales of savagery, horror, and suspense for their time.

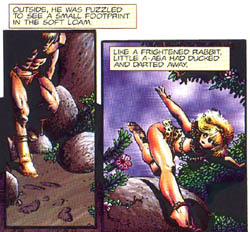

Spear and Fang Roy Thomas: writerRichard Corben: artist Eric Hope: color and rendering "Spear and Fang" first appeared in the July 1925 issue of Weird Tales magazine. This story was Robert E. Howard's first professionally published tale, and he wrote it when he was nineteen. It is a tale of a Cro-Magnon cave man, his female admirer, a competitor for her affections, and a savage battle against a more beastly Neanderthal man who also has designs on the woman. Initially, the distinct style of the artwork seemed a bit hokey; more akin to the wacky art found in the old Mad Magazines -- bulky, stretched, distorted, out of proportion -- but after a while I got used to the style and, when considering the primitive subject matter, this art style seems somehow appropriate. I then tried to sit back and let the story flow. Unfortunately, that proved impossible. The story is afflicted with poor transitions from scene to scene, which serve to stop the action and shock the reader out of the drama. The coherence and continuity of the story is poor as well. Many times I asked my self, "who is this guy?", "why is he there?," "why would he do that?," "what is she doing there?" etc. Then intertwined with all this is a lack of character development which prevents the reader from caring about the characters. Most of this could easily have been avoided with three or four additional panels and about 20 additional words from Howard's text. Here's some specifics:

"Spear and Fang" was a very short tale to begin with, and Howard's text was already condensed for a short story. To condense it further for adaptation tempts fate, but it is nevertheless possible to do... up to a point. It is important to depict the most important scenes in the story, but it is equally important to include story text which develops characters, builds the climax, and provides continuity and coherence throughout the story. Without these things, the dramatic impact of the story is either diminished or completely obliterated. A word of advice for future adaptations of Howard's work... err on more rather than less. And lastly, what would a review of this story be without a purist nit-pick? Howard fans might be interested to know that A-aea's hair color in the original story was black, and not blonde as Myth Maker depicts.

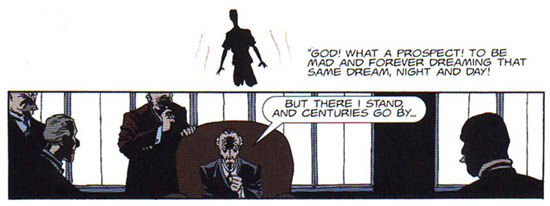

Dream Snake Roy Thomas: writer "Dream Snake" was first published in Weird Tales magazine, February 1928. The story is an account of an old man who has been plagued by the same nightmare every night since he was born. He relates his nightmare to a group of friends, and that very night his fear finally catches up with him. It is a story of terror and dread that reaches from the outer gulfs of the cosmic unknown and into the mind of mankind, or the worldly manifestation of man's own nightmares. About the story Howard remarked, "The subject of psychology is the one I am mainly interested in these days. The story ... was purely a study in psychology of dreams."1 The artwork for "Dream Snake" is stylish and dramatic, conveying the mood of foreboding fear well. Even though the story does an admirable job of conveying the fear felt by the main character, the story missed the opportunity to play with the readers' minds and capitalize on their own fear. "Dream Snake" can be taken superficially as a straight supernatural thriller where a man's nightmare mystically comes to life and kills him, or as a more complex psychological thriller where instead of some supernatural being it is in fact the man's own mind which is stalking him, not necessarily driving him insane but pressing him to see that he is already insane. It is not the snake which he is afraid of, but rather the prospect of insanity. To quote from the original text: "...I can feel my sanity rocking as my sanity rocks in my dream. Back and forth it totters and sways until the motion takes on a physical aspect and I in my dream am swaying from side to side." The serpent is the physical manifestation of insanity itself. Swaying and rocking like a serpent, and relentlessly pursuing the man. Although the mood of fear in the story was good, the sense that it was a frantic, unrelenting terror could have been better achieved by telling the reader, as Howard did, that the man felt as if the snake was always at his back and that the snake was already in the bungalow, thus increasing the threat. Keeping in mind the symbolism that the snake represents insanity, think of the bungalow as the man's mind in the following passage: "...for a horrible obsession has it that the serpent has in some way made entrance into the bungalow, and I start and whirl this way and that, frightfully fearful of making a noise, though I know not why, but ever with the feeling that the thing is at my back."

The man knows that if he ever saw the serpent in his dream that he will go insane. But what if the man was already insane? The snake represents insanity on one level, and, with a nice twist of irony, the snake could also represent a part of the mind that is trying to tell him that he is already insane. The man tells us that the most horrible prospect would be to go insane and be forced to dream this same dream day and night... and yet isn't that exactly what the old man has been doing all his years? Obsessed with, or possessed by this merciless serpentine nightmare?

Although the opportunity to heighten the terror in the story was missed, it is the ending of the story which robbed it of all its impact. Essentially, the entire story was designed to build up to the final dramatic climax. The foundation for the climax is laid down sufficiently in the adaptation, but unfortunately the ending was cut short, as if an axe-man had chopped off its legs just as it managed to rise. Howard's original ending is almost too short for the story, and contains only the bare minimum for a dramatic ending. The comic book ending is even shorter and it lost much with the editing. Compare the two endings: Robert E. Howard: "At regular intervals I dream it, and each time, lately" -- he hesitated and then went on -- "each time lately, the thing has been getting closer -- closer -- the waving of the grass marks his progress and he nears me with each dream; and when he reaches me, then--" He stopped short, then without a word rose abruptly and entered the house. The rest of us sat silent for a while, then followed him, for it was late. How long I slept I do not know, but I woke suddenly with the impression that somewhere in the house someone had laughed long, loud and hideously, as the maniac laughs. Starting up, wondering if I had been dreaming, I rushed from my room, just as a truly horrible shriek echoed through the house. The place was now alive with other people who had been awakened, and all of us rushed to Faming's room, whence the sounds had seemed to come. Faming lay dead upon the floor, where it seemed he had fallen in some terrific struggle." Cross Plains Comics: "At regular intervals I dream it, and each time, lately, the thing has been getting closer -- closer. The waving of the grass marks his progress and he nears me with each dream. And when he reaches me -- then--" Without a word he rose and entered the house. That night, we other guests woke suddenly as first a hideous laugh, then a truly horrible shriek echoed through the house. All of us rushed to Faming's Room. He lay dead upon the floor, where it seemed he had fallen in some terrific struggle." The key dramatic information missing in the Cross Plains Comics version is the description of how the man, Faming, rose abruptly, how his laugh sounded as if a maniac uttered it, and how his scream echoed through the house. Incidentally, this is the only place in the entire comic book where new text was used to replace the original text. Needless to say, the ending should have been lengthened with both more text and several additional art panels. An image of the man rising quickly, some snake-like or serpentine panels of something unseen slithering through the halls as the men slept, and a long shot of the house as the scream ripped through the air probably would have saved the story, not to mention an image of Faming's death face! As it stands in the comic book, the story is not only anti-climatic, but it falls on the ground with a resoundingly flat and boring thump. Unfortunate.

Dermod's Bane Roy Thomas: writer

"Dermod's Bane" is the best re-telling of the three stories Cross Plains Comic offered in the first issue of Myth Maker. The art is excellent, stylish, and brooding. The text was taken directly from the original story, and included all the appropriate dramatic clues. The story adaptation is excellent, but the story itself is not one of Howard's best. Trite and worn out by over use, Howard's wording, scene settings, and plot are not bad, but not exciting either. This was yet another of the shortest stories from Howard's repertoire.

Men of the Shadows (story introductions) Roy

Thomas: writer "Men of the Shadows" is the title of the framing sequences which introduced each story. This framing sequence is an original creation by Roy Thomas, and includes characters from various Howard stories and poems. The art has a flowing, surreal feel about it, and the artwork for the Moon Woman was excellent and contrasted superbly with the rest of the book. In general, however, the story introduction(s) was hokey, contrived, and adolescent melodrama. I didn't really care for the focus on suicide throughout the sequence and felt the emphasis on the subject was in bad taste. Nor did I, as a reader, feel the slightest curiosity as to why the four characters had been called together... there was no reason for us to care and it was simply an annoying gimmick. On the other hand, the one page at the end where we see Robert E. Howard typing out the beginning of his poem, "The Tempter," I thought was terrific! The art and imagery I mean. If Cross Plains Comics can keep this idea going, that we are reading the stories as REH types them out or dreams them up, I think they'll have a winner! It would be like having a window into history. REH's letters would be an excellent source for dialogue in the framing sequences! He was heavily into dream imagery and trying to divine their meaning. This will work so long as Cross Plains Comics does not turn REH into an actual character, but instead lets his letters talk for him. I don't think anyone wants to see Howard as a figment of someone else's imagination. Some technical issues with the framing sequence arise out of the

use of bits and pieces of Howard's poetry. Not only were many of Howard's

best poems broken up and used simply for effect, but they weren't even

credited! Using pieces and fragments of Howard's work in a derivative

story might seem like a good idea to begin with, but the drawback

is that breaking up Howard's work like this precludes publishing the

same Gutting an author's work is a common practice in motion pictures when a work is adapted into the film medium. The script writer cannibalizes the original author's work, searching through the entire breadth of the author's literature and taking bits and pieces from each story, novel, or poem and fitting them all into a single movie. If for all time there was only going to be one movie, then including every recognizable scene from every original story or poem wouldn't be a terribly bad strategy (purely from a production standpoint), but what if the movie is successful? Then what do you do for a sequel? Unfortunately, all the good stuff was used up in the first movie, and you can't go back to the original texts because the audience would notice the scenes you'd want to show them again. So what do you do? Either nothing, or hire a writer to write a completely new pastiche... which usually has the effect of completely excising any inklings of the original author's work, characters, or vision -- and producing a flop. It's a practice that not only disrespects the original work, but it's just bad mojo. Cross Plains Comics has now started down this road of hodgepodge story introductions, but CPC has the opportunity to reverse course and present Howard's work with respect and triumph. All of Howard's work are examples of art and artistry, and should not be treated as mere "material" to be manipulated, used, and thrown away. It is not only virtuous but also prudent to adapt Howard's work as whole pieces. So that they may receive proper credit, here's the list of Howard's poems which appeared in the "Men of the Shadows" story introductions and a brief description of each poem:

The complete text for all of these poems can be found in the book, Always Comes Evening, edited by Glenn Lord. Another blunder was crediting Mr. Thomas for adapting the "Men of the Shadows" framing sequence that ties all the stories together. It's obvious to anyone who is familiar with Howard's work that the story introduction sequence is an original Thomas creation, and not a Howard creation (even if there are some fragments of Howard's poetry littered throughout the sequence). In this case, Thomas should have been credited as "writer" and Howard's poem fragments should have been credited to Howard. The word "adaptation" actually implies that Howard wrote the original framing sequence for the comic book and Mr. Thomas merely adapted it... which is untrue, confuses readers, and obscures and misrepresents Howard's work. At the same time that the credit slights Howard it also impinges on Mr. Thomas' rights by implying that Howard wrote the new sequence, and improperly deflecting credit for Mr. Thomas and his creative effort. And lastly, it might be of interest to Howard fans to note that the James Alison character was in fact a cripple in Howard's stories with a lame leg, and not the picture of health that Myth Maker's "Men of the Shadows" depicts. Who did the research for this book? Or was the character originally intended to depict Robert E. Howard himself, and the character's name changed at the last minute? A good call, if true.

Poetry Men of the Shadows (poem) Roy

Thomas: editor/source material "Men of the Shadows" is a poem which was originally embedded in the beginning of the Bran Mak Morn story of the same name. The poem was first published, however, in a book of Howard's verse titled, Always Comes Evening, in 1957. On odd textual mystery here is that the following two lines seem to have been deleted from the Always Comes Evening printing of the poem: Sailing o'er seas unknown According to Glenn Lord, the previous literary agent for the Howard estate, the two lines were omitted by Oscar Friend (of Otis Kline Associates) in 1956 when he sent Mr. Lord the poems for inclusion in Always Comes Evening. These lines do, however, appear in the first published version of the tale found in the paperback, Bran Mak Morn (Dell, 1969), and every printing of the story thereafter. The "Men of the Shadows" poem is adapted nicely with a mosaic of a wonderful drawing by John Bolton, and even a stylish photograph of Stonhenge by Barbara Gillespie. What might go unnoticed by a casual reader is that all the art surrounding this poem is in fact bits and pieces of one drawing, arranged by Rafael Kayanan into a dynamic, eye moving collage. As nice as the artwork is, it is nevertheless overshadowed by sloppy typos and the unthinkable combination of three separate poems into one. For some unfathomable reason Mr. Thomas decided to combine the primary poem, "Men of the Shadows" with "Chant of the White Beard" and "Rune." These last two were taken from the middle of the story, "Men of the Shadows," and are in fact not poems at all but rather parts of an incantation spoken by the wizard in the story. Glenn Lord broke this chant up into two poems for Always Comes Evening, although I don't really see the reason for the separation. To me, both pieces are just one chant. Although I don't see any problem with combining these last two bits of chant, the combination of the chant with the "Men of the Shadows" was a mistake. "Men of the Shadows" has a definite and distinct theme and climax... whereas the chant is merely that, an incantation, with little if any point other than to call upon mystic powers. They are clearly not meant to be merged together as one poem. To add insult to injury, the poem "Song of the Pict" which also appears in the story is conspicuously left out of Myth Maker. Combining "Men in the Shadows" and the chant was a serious mistake and just plain sloppy. Worse still, "Chant of the White Beard" and "Rune" were not even credited, leaving the reader to believe they were reading only one poem. The reader may like to know that the true poem, "Men in the Shadows," ends with the line, "The last of the Stone Age men." This mistake indicates a slipshod work ethic on the part of the editor, who should be checking for such things. In order to have avoided this problem, each poem should have been typed separately and titled individually. Proofreading the poem's text for typos would have been a good idea too, as there are several mistakes. In the final analysis, being mindful and careful with Howard and his work doesn't negatively affect the dramatic impact of the comic book. In fact, it is likely to heighten the drama and quality of the books... and it certainly would benefit Cross Plains Comics in the long run.

An Open Window (poem) Rafael Kayanan: artist The version of "An Open Window" found in Myth Maker was first published in the September 1932 issue of Weird Tales magazine. The poem can also found embedded in the story, "The House," which was a tale Howard left unfinished. In the story, the poem is credited to an eleven year old boy, Justin Geoffrey, who was possessed by uncommon genius, cosmic lore, and ghastly nightmares; and who eventually ended his career many years later as a poet who had gone quite mad. Howard's story fragment for "The House" was posthumously completed by August Derleth, re-titled "The House in the Oaks," and this completed story was published for the first time in Dark Things (Arkham House, 1971) and later in Black Canaan (Berkley, 1978). An interesting little bit of trivia is that the poem published in Weird Tales differs by one word in the second line (and a few commas) from the poem embedded in "The House in the Oaks." The word "things" is used in Dark Things, while in Weird Tales the word "Shapes" is used. Although we can't be certain, it is likely that Howard wrote the story fragment, "The House," in the later half of 1931 while also writing other Lovecraft type horrors such as "The Black Stone," "The Thing on the Roof," and "The Horror from the Mound." Howard often took previously written poems from unsold stories and polished them for submission to Weird Tales. Presumably, this is what Howard did with "An Open Window," and it would explain the differences in the poem. "An Open Window," as drawn or adapted by Rafael Kayanan, is an exceptional piece of work! Although the font used for the poem text is a little small, the full page of artwork presented with the poem wonderfully conveys the brutal, hostile savagery depicted in many a Howard yarn with the calm, quiet loneliness of Howard's life as a writer in a small, Texas town. Kayanan's artwork is dark, moody, and thoughtful. Kayanan also did his homework, as all the items seen in his drawing are authentic Robert E. Howard artifacts, including the Howard home. Another interesting, and perhaps coincidental association is that the text of the poem can also be seen to describe the "colossal" face by John Bolton which is prominently displayed on the cover of Myth Maker. It seems somehow appropriate that "An Open Window" is on the last page of Myth Maker and, as we close the book, Bolton's "face" comes into view. Although probably unintentional, it is not without charm. Bravo!

Articles "Three Years in the Making" by Richard Ashford, managing editor of CPC, is a well written introduction to how Cross Plains Comics came into being, and a description of some of the trials and tribulations overcome while bringing this new comic book company into existence. "From Cimmeria to Cross Plains" by Roy Thomas is an all too brief article which is unfortunately marred by an ill considered slur directed toward die-hard Robert E. Howard fans who are sometimes called "purists". Not only does Thomas's comment of "muddle-headed purists" lean toward alienating the very people he should be courting, but it is hardly ever appropriate or beneficial to sling insults or air one's dirty laundry in public. Mr. Thomas should never have been allowed to use Myth Maker as a personal forum to vent his spite and prejudice. Truly bad taste. Perhaps the most disturbing implication of Mr. Thomas' statement, however, is that "purism" or artistic integrity is something to be ridiculed and dismissed, rather than something to strive for and protect. "Novalyne Price Ellis: A Short Biography" by Rusty Burke is a thoughtful and moving tribute to a woman who gave us more about Howard's life with her wonderful memoir, "One Who Walked Alone," than any other individual living or dead. The article is well written and a true gem.

Layout, graphic design, and color schemes When one touches the book and feels its weight in one's hand, the pure quality of the heavy paper and vibrant inks makes one catch their breath. With an unusually heavy 60 pound cover stock and an artistry of design and layout unmatched by any other, this 64 page Myth Maker feels and looks more like a fine magazine than a comic book. It certainly is worthy of a wider distribution to mainstream book stores and stands. The credit for the truly excellent, first rate job on Myth Maker's layout, graphic design, and color schemes goes entirely to Rafael Kayanan! A couple of the other artists featured in the book also did a grand job in layout and presenting their panels in the stories. These contributions are the high point of the magazine! Innovative, stylish, classy, dramatic, and unlike any mere superhero comic book! Well done!

Conclusion From what I've written so far you may be under the impression that I don't care much for Myth Maker, but that couldn't be farther from the truth! Aside from the tasteless and disrespectful story introductions, every mistake I've mentioned would easily be remedied with only a little more attention to detail for future issues. Further, the assemblage of artwork mingled with the tremendous graphic design and layout in the book is truly outstanding! Every story and poem was drawn by a different artist in completely different styles. This mixture of styles not only offers something for everyone, but presents such a wide range of stylistic imagery that I'm hard pressed not to think of it as a smorgasbord of gourmet delicacies! The choice of stories to include in the first issue must have been difficult, but I can't help thinking that CPC could have chosen better examples of Howard's work. About "Spear and Fang," Roy Thomas writes2: "...it was far from [Howard's] best work," and "...my only regret is that the story wasn't even longer." Mr. Thomas echoes my own thoughts here, but I would have said the same thing about all the stories in Myth Maker. All three stories were extremely short and took only a few fleeting minutes to read. I would have liked the action and adventure of each story to have lasted a little longer. Perhaps the next Myth Maker will include one or two longer stories? In any case, Cross Plains Comics should be congratulated for standing up for artistic integrity and publishing Howard's stories nearly word for word, with very few changes. Myth Maker is an excellent first try, and I have learned from the people at CPC that nearly all of the errors in Myth Maker were just that... mistakes, accidents, oversights. To me, these things are understandable, forgivable once or twice, and certainly correctable! However, more importantly, the will is there to do better, to improve, to correct past mistakes and to make future products better than past products! As long as CPC retains this excellent attitude they will find me to be a staunch supporter. Although probably put together as a last minute rush job, Myth Maker nevertheless shows the promise of a top notch magazine.

Footnotes:

|